Art Perception: How We See, Feel and Understand Visual Expression

What Art Perception Means in Practice

Art Perception is the process by which viewers transform visual input into meaning. It combines sensory reception with memory emotion and cultural knowledge to produce an interpretation that is unique to each observer. When someone stands before a painting sculpture or installation they do far more than record color or form. They make connections with personal experience historical context and the conventions of visual language. Understanding this process helps artists curators educators and collectors to shape how art is presented discussed and preserved.

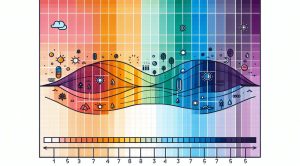

The Science Behind Visual Interpretation

At the core of Art Perception are basic neurological operations. The eye captures light and sends signals to the brain where pattern recognition depth cues and color processing take place. Beyond these early stages the brain uses prior knowledge to fill gaps and to prioritize certain elements. Attention plays a large role. A viewer may notice a single bright area before they register subtler details. Memory and emotion then guide whether the work is experienced as comforting challenging or mysterious. This chain of operations explains why different viewers can come away from the same work with very different impressions.

Historical Perspectives on How People Saw Art

Across time cultures have shaped how their members perceive art. In some eras moral and religious frameworks dictated which elements were important. In other moments innovations in technique changed perception. The introduction of linear perspective in the early modern period transformed spatial interpretation turning flat surfaces into apparent three dimensional space. Later photographic reproduction shifted attention toward the captured moment and the idea of realism. Each change in material technology and visual grammar altered the default expectations of viewers and contributed to evolving modes of Art Perception.

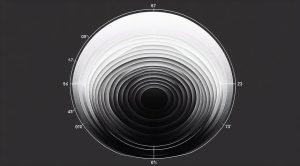

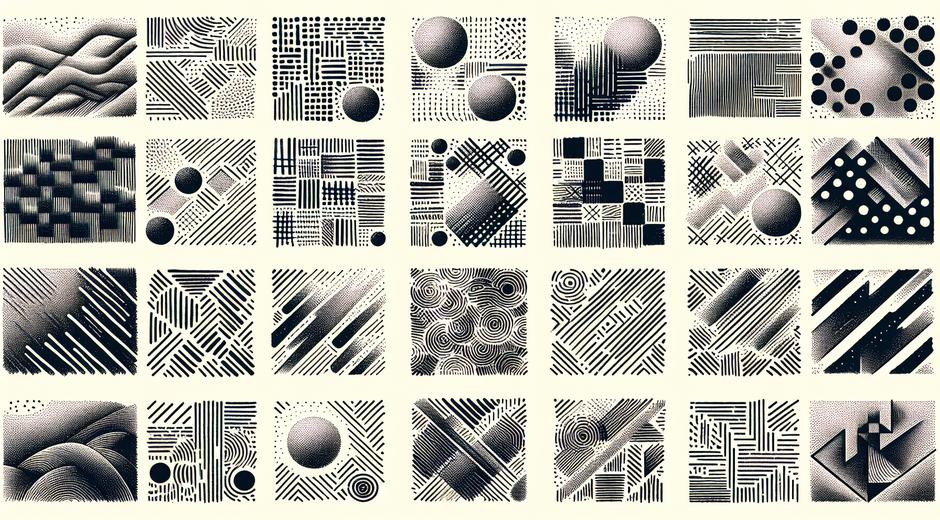

Techniques Artists Use to Guide Perception

Artists are not passive recipients of perceptual rules. They actively shape the viewer experience by manipulating composition color scale and contrast. A strong focal point can direct attention immediately while rhythmic repetition can create a sense of movement. Scale can evoke awe or intimacy. Color temperature can set mood. Light and shadow structure volume. Even omissions can be powerful. By knowing how perceptual systems operate artists craft moments of surprise insight and emotional resonance. Understanding these methods is valuable for anyone who wishes to engage more deeply with visual work.

Context and Cultural Framing

Context alters perception more than many people realize. A painting shown in a private home will be read differently from that same painting displayed in a museum gallery with scholarly labels. The presence of text image placement lighting and surrounding works creates a narrative that nudges interpretation. Cultural background provides a set of signs and symbols that the viewer decodes. Consequently curators and educators must think deliberately about framing and narrative to ensure that intended meanings are communicated without erasing viewer autonomy.

How to Improve Your Own Art Perception

Anyone can sharpen their Art Perception by practicing certain habits. Slow looking is essential. Spend several minutes with a single work noting changes in what you notice over time. Ask open questions like what is the first thing I see and what else appears after focused attention. Note emotional responses and try to trace them to specific formal elements. Read about the context and about the artist to expand the interpretive palette. Discussing works with others reveals alternative readings and challenges assumptions. Over time these practices create a richer and more flexible perceptual skillset.

Perception in the Digital Age

Digital reproduction has both expanded access to art and introduced new perceptual dynamics. On a screen scale detail and texture may be lost while color shifts can alter mood. Still digital platforms allow layered narratives linking archival material interviews and curatorial notes to enhance understanding. They also invite new forms of interactivity where users control zoom orientation and sequence. For those who study perception the digital realm offers a laboratory to observe how changes in presentation change interpretation. Institutions and content creators must balance fidelity with the affordances of the medium to preserve meaning.

Practical Implications for Curators and Educators

Curators shape collective perception through selection display and interpretation. Lighting choices and wall color influence how surfaces appear. Placement relative to other works creates dialogues that can highlight contrast or continuity. Labels and audio guides supply context but they can also limit imagination if they impose a single authoritative reading. Educators can use insight from perceptual science to design programs that encourage active engagement. By training viewers in slow looking and comparative analysis they increase attention and foster a deeper relationship with art.

Art Perception and Emotional Response

Emotions are fundamental to how we evaluate art. The same formal structure that draws attention also triggers feelings based on personal memories and cultural associations. A low horizon and muted palette might evoke calm in one viewer and melancholy in another. Recognizing the role of emotion helps us understand why debates about value and intent can be so passionate. It also opens pathways for therapeutic uses of art where perception becomes a channel for reflection and healing.

Case Studies in Perceptual Innovation

Many contemporary artists design projects that interrogate perception itself. Works that shift under changing light or that require viewer movement to resolve an image call attention to the act of seeing. Installations that incorporate sound or tactile elements expand perception beyond the visual and invite multi sensory engagement. These experiments remind us that perception is not fixed. It is a dynamic interchange between viewer and work where meaning is negotiated in the moment.

How Musea Time Supports Deeper Viewing

For readers who wish to continue their exploration of Art Perception and related topics there are many resources. The site museatime.com offers articles guides and curated collections that model slow looking and critical reflection. Exploring those materials can provide practical exercises for individuals groups and classrooms as well as background essays that enrich contextual knowledge.

Unexpected Connections Between Visual Perception and Everyday Domains

Perception principles learned from art often apply in surprising areas such as product design spatial planning and vehicle ergonomics. For those researching how visual cues and human attention affect interaction with machines and environments a number of resources explore applied perception beyond galleries. If your interest extends to how motion space and visual focus interact in everyday transport situations you may find useful background at AutoShiftWise.com which discusses ergonomics and design considerations that influence how users perceive dynamic systems in motion.

Conclusion: Perception as an Active Practice

Art Perception is not a passive reception of images. It is an active skill that can be taught sharpened and deployed to reveal deeper meanings. By learning to attend to formal elements context and emotional response viewers gain access to richer interpretive possibilities. Artists and curators who design with perceptual science in mind create experiences that engage more people in more profound ways. Whether you are visiting a gallery or viewing work on a screen cultivating a habit of attentive curious looking will transform how you experience visual art.