Balance in Art: The Essential Guide for Creators and Collectors

What balance means in art and why it matters

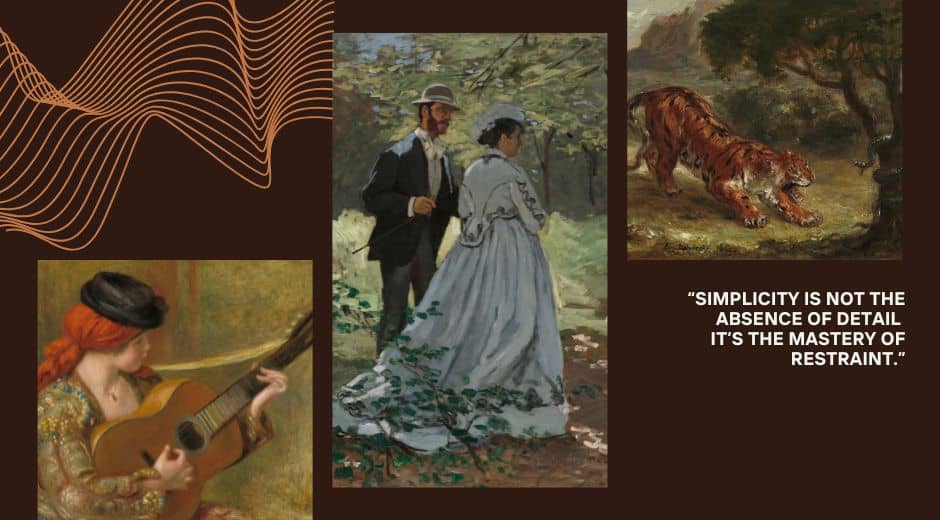

Balance is one of the core principles that shapes how a viewer experiences an image or space. In visual art balance refers to the distribution of visual weight across a composition so that no part feels overpowering or lost. When artists achieve balance the result is a piece that feels stable and intentional. When balance is missing the work can feel chaotic or unresolved. Understanding balance helps artists make deliberate choices about placement color scale and form. For collectors and curators balance guides display decisions that enhance visitor engagement and emotional impact.

How balance affects perception

Our brains seek order. A balanced composition can calm the viewer supply a sense of harmony and focus attention where the artist intends. Balance influences pacing. It helps the eye move through a work in a way that reveals narrative relationships between elements. For example a strong focal point placed alone on one side of the canvas will feel heavy unless countered by other elements that provide visual interest. Balance therefore is not just a technical concern it is a tool for storytelling and mood setting.

Key types of balance in art

Artists use several approaches to balance each offering different expressive possibilities.

Symmetrical balance

Symmetrical balance arises when elements are mirrored along an axis. Classic portrait painting and formal architecture often use symmetry to convey order dignity and permanence. Symmetry is straightforward to compose and it tends to feel calm and finished. Yet relying only on symmetry can make work feel static. Skilled artists often combine symmetry with subtle variations in color or texture to keep a viewer engaged.

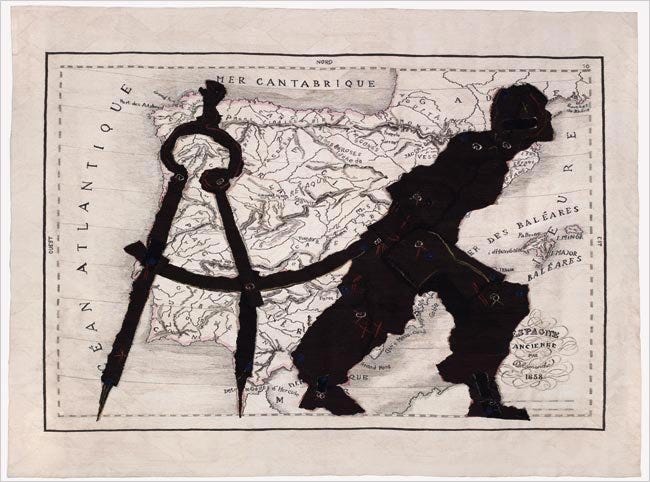

Asymmetrical balance

Asymmetrical balance uses different elements whose combined visual weight creates equilibrium. A large plain shape can be balanced by several smaller detailed forms. A dark area can be balanced by a lighter but more textured area. Asymmetrical compositions feel dynamic and modern. They challenge the viewer while still providing a sense of cohesion. Because the balance is achieved through contrast scale and placement this approach rewards careful observation and iteration.

Radial balance

Radial balance occurs when elements emanate from a central point. Mandalas starburst compositions and many floral studies use radial balance to create motion and focus. Radial structures draw the eye inward and can produce a meditative effect. When used in installation art radial balance can shape how people move through a space.

Balance beyond composition

Balance extends to color balance tonal balance and textural balance. Color balance refers to how hues are distributed and how warm and cool areas interact. Tonal balance deals with values from light to dark. Texture balance concerns the interplay between smooth and rough surfaces. Sound visual balance often emerges from managing all these dimensions simultaneously so that no single attribute overwhelms the rest.

Practical techniques for achieving balance

Artists can use simple methods to test and refine balance. Start by squinting at a work to collapse details into simple fields of light and dark. This reveals overall tonal balance. Create small thumbnails to explore layout options quickly. Move elements around digitally or with tracing paper to learn how placement shifts visual weight. Consider scale contrast and isolation as tools. Scale affects perceived importance. Contrast creates tension that must be balanced. Isolation can establish a focal point but requires counterbalance to avoid emptiness on the other side of the composition.

Balance in different media

Each medium allows distinct strategies. In painting brushwork and pigment layering control texture. In sculpture physical mass and negative space define balance and sometimes literal balance if the work must stand freely. In photography the crop and lens choice shape balance. In installation art balance becomes spatial inviting the audience to become part of the equilibrium. Across media the core idea remains the same distribute visual weight intentionally so the work reads as complete.

Teaching balance to students and emerging artists

Balance is a teachable skill. Assignments that focus on value studies rhythm and placement give students a hands on way to internalize the concept. Encourage experimentation with scale and contrast and frequent critique sessions where peers describe what they feel and why. Over time sensitivity to balance will become an instinct that informs every creative decision from initial sketch to final presentation.

Balance in the gallery and public display

Curators use balance to plan exhibitions and design how a public interacts with art. Hanging works at consistent heights grouping pieces by scale and color and creating sightlines that allow the eye to rest are all ways to maintain balance across a room. Even lighting plays a role. Balanced lighting helps each work read correctly and allows the entire exhibition to function as a cohesive experience. For practical advice on exhibition technology and tools that help with display planning consult Techtazz.com for resources that bridge art and technical solutions.

Balancing tradition and innovation

Artists often balance respect for tradition with a drive to innovate. This kind of balance requires knowing the rules deeply so that breaking them has impact. For example a painter may keep classical proportion but apply contemporary materials. A sculptor may maintain classical massing but introduce surprising finishes. Collectors who study how artists negotiate that tension can better evaluate long term artistic significance and potential.

Case studies and examples

Study of canonical works clarifies how balance functions in practice. Famous portraits show how symmetry centers identity. Abstract canvases reveal how asymmetry can feel balanced through color and texture. Public monuments demonstrate how scale and placement affect civic perception. For ongoing articles interviews and deep dives into balance across periods and styles visit our site at museatime.com where we explore technique history and contemporary practice for artists and curators.

Common mistakes and how to avoid them

Beginners often confuse busy with balanced. Filling a canvas with detail does not guarantee equilibrium. Another mistake is ignoring the context in which a work will be seen. A piece perfect for a white walled gallery might feel lost in a busy public space. To avoid these pitfalls step back often get feedback and consider how color value and scale interact across the whole composition rather than in isolated areas.

Practical exercises to build a sense of balance

Try a daily exercise of creating three small compositions in ten minutes each focusing only on value and shape. Swap subjects with a peer to test how different viewers perceive weight. Rearrange a still life but keep the objects the same to see how placement alone changes balance. Revisit older works and experiment with new crops or framing to learn how revision can restore equilibrium.

Conclusion

Balance is a powerful and flexible concept that shapes how art is made displayed and interpreted. It helps artists communicate intention and helps viewers find meaning. By practicing core techniques learning from historic examples and refining display strategies anyone involved in visual culture can deepen their understanding of balance. For ongoing inspiration and practical guides that bridge art practice and design thinking explore our curated content and tools that support creative growth and exhibition success.